Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is the result of infection with the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi. The disease is transmitted by infected ticks that also feed on mice and deer. The tick can often be found still attached to the skin. Most cases of Lyme disease occur in the spring and summer months. Lyme disease is treated with antibiotics.

There are 3 phases of Lyme disease:

- Early localized – Symptoms start a few days to a month after a tick bite. There may or may not be the classic bull’s-eye rash.

- Early disseminated – Multiple skin lesions are seen, along with flu-like symptoms and head, neck, and joint pain. There may also be heart or nerve symptoms as well as arthritis, which can develop over a few months to up to 2 years after the initial infection.

- Late – The heart, joints, and nervous system can be affected. Symptoms can develop over a few months to years after the initial infection and may be difficult to treat.

Who's At Risk?

Lyme disease is transmitted by infected ticks and cannot be spread by person-to-person contact. Children who spend a lot of time in or near wooded areas are at a higher risk for contracting Lyme disease. Lyme disease is reported most often in the Northeastern United States from Maine to Maryland, in the Midwest in Minnesota and Wisconsin, and in the West in Oregon and Northern California. It has also been reported in China, Europe, Japan, Australia, and parts of the former Soviet Union.

Signs & Symptoms

Sometimes the tick can be found attached to the skin. When there is no tick present, the site of tick attachment may not be visible.

Erythema migrans, the classic flat, red bull’s-eye lesion on the skin, will appear days to weeks after the bite. In darker skin colors, the red color may be harder to see, or it may appear dark red, purple, or brown. Note; however, that about 25% of those affected never get this lesion. Some may complain of flu-like symptoms, including fever; head, neck, and joint pain; and generalized muscle pain. The lesion will resolve without treatment in about a month.

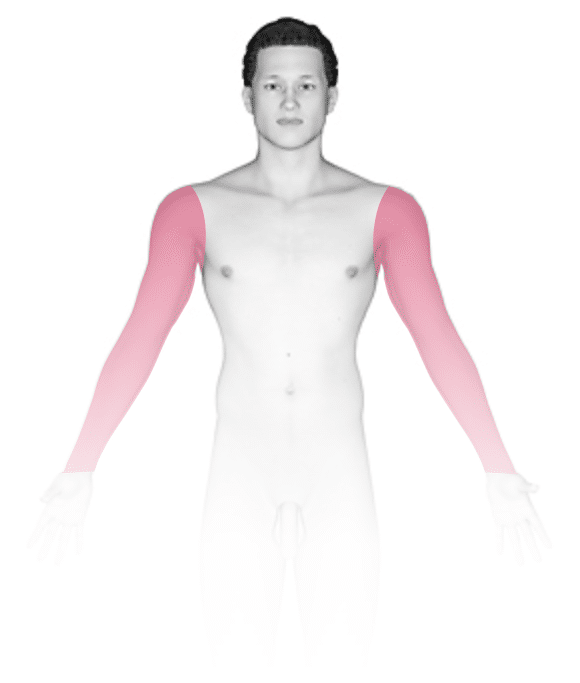

Weeks to months later, the bacterium can affect the joints, heart, and nervous system.

In the late phase of Lyme disease, there can be an abnormal heart rhythm. The face can become paralyzed (facial muscle paralysis), and your child can have confusion and abnormal sensations of the skin such as numbness, tingling, a prickling sensation, or pain. There can be inflammation in the joints, or arthritis, beginning with swelling, stiffness, and pain, commonly affecting the knees.

Self-Care Guidelines

If you have found a tick on the skin and removed it, save it in a jar of alcohol for identification.

Ticks begin transmitting Lyme disease about 24-48 hours after attaching to the host. You can reduce your child’s chances of getting Lyme disease by removing the tick within 48 hours.

To remove the tick, you will need tweezers and isopropyl alcohol.

- Sterilize the tweezers with alcohol and make sure to wash your hands. You should not clean or disturb the skin near the tick.

- Grasp the part of the tick that is embedded in the skin with the tweezers, not the body where you may see tiny legs. If necessary, have someone else hold the area with the tick so that the child doesn’t jerk away.

- The tick will likely be firmly embedded. Pull it outward in one motion. Do not twist or jerk the tweezers. Do not apply anything to the tick that you think may help it come out smoothly as this may result in a part of the tick being left in the skin.

- Clean the bite wound with alcohol. Children have very sensitive skin, so you may notice an immediate swelling where the tick once was. If you are not sure the entire tick has been removed, see your child’s medical provider.

Treatments

Lyme disease can be treated and cured with one of several oral antibiotics for 3-4 weeks. The skin rash will go away within a few days of beginning treatment, but other symptoms may persist for up to a few weeks. In severe cases of Lyme disease where the nervous system is involved, the antibiotic may need to be given intravenously. In late-stage Lyme disease, symptoms may not go away completely but should improve.

Visit Urgency

If you suspect your child has had a tick bite and may have contracted Lyme disease, call their medical professional. A single dose of antibiotics can be given in the first 72 hours after a tick bite to prevent Lyme disease, if deemed appropriate by the medical professional.

If a rash or other early symptoms of Lyme disease develop, see a medical professional immediately.

References

Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018.

James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, Rosenbach MA. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019.

Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

Paller A, Mancini A. Paller and Mancini: Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2022.

Last modified on June 14th, 2024 at 12:48 pm

Not sure what to look for?

Try our new Rash and Skin Condition Finder