Cellulitis

Cellulitis is a bacterial infection that can appear as a red, swollen area of skin that may feel warm to the touch. The infant may also have a fever or seem fussy.

The most common bacteria causing cellulitis in babies is Streptococcus. While it may be hard to see, there are often very small cracks (fissures) in the skin that the bacteria enter through.

While the infection may just be on the top skin layer (superficial), it can also affect deeper tissues, involving the muscle, bone, and possibly blood. It is important to recognize cellulitis as early as possible so it can be treated with antibiotics. If left untreated, cellulitis may turn into a life-threatening condition.

Who's At Risk?

Cellulitis occurs in all ages. Babies may be get cellulitis from a small break in the skin, such as from an accidental injury by a caregiver or by the infant causing self-injury (such as from scratching). Babies’ still-developing immune systems may have trouble fighting off cellulitis infections.

Signs & Symptoms

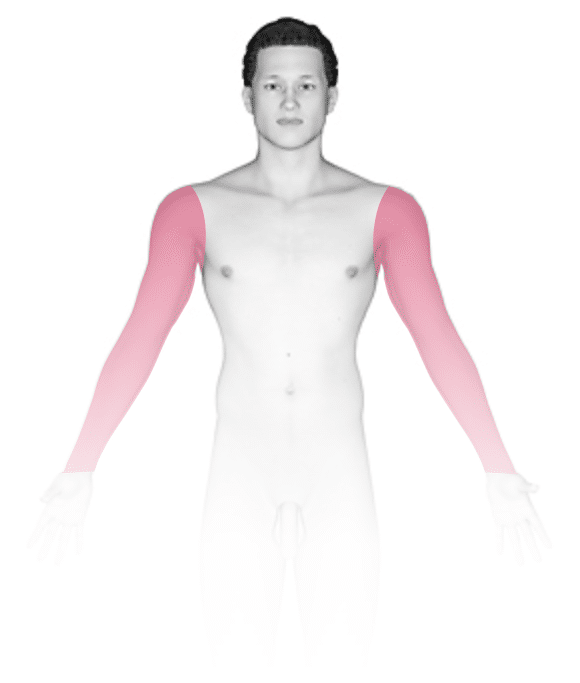

The most common locations for cellulitis include the:

- Lower legs.

- Arms or hands.

- Face.

Cellulitis often initially appears as slightly inflamed skin. The affected skin quickly becomes swollen, warm, and tender, and the affected area increases in size as the infection spreads. In lighter skin colors, the area may be any shade of pink or red. In darker skin colors, the redness may be harder to see, or it may appear more purple or dark brown. Occasionally, red streaks may radiate outward on the skin from the site of the cellulitis. Vesicles (small blisters) or pustules (small pus-filled lesions) may be present.

Cellulitis may occur with swollen lymph nodes. Fever and chills are common.

Self-Care Guidelines

There are no self-care treatments for cellulitis. See your baby’s medical professional immediately, or take them to urgent care or the emergency room.

Treatments

Although your baby’s medical professional may easily diagnose cellulitis, they might order other procedures, such as a blood test or bacterial culture, to find out what type of bacteria may be causing the cellulitis.

While waiting for the results from the bacterial culture, the medical professional may recommend treatment at a hospital for observation and so the baby can receive injected (intravenous) antibiotics. Based on the culture results, they may change the antibiotic, especially if your baby is not improving on the one initially prescribed.

The medical professional may prescribe antibiotics such as:

- Vancomycin (eg, Firvanq, Vancocin).

- Cefotaxime (eg, Claforan).

- Gentamicin.

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in babies 2 months and older.

Visit Urgency

If your baby develops a warm, enlarging area on the skin that is either red or darker than the surrounding skin, see their medical professional as soon as possible. If your baby also has a fever or if the area is on their face, you should take them to urgent care or the emergency room.

If your baby is currently being treated for a skin infection that has not improved after 2-3 days of antibiotics, return to their medical professional.

References

Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018.

James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, Rosenbach MA. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019.

Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

Paller A, Mancini A. Paller and Mancini: Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2022.

Last modified on June 14th, 2024 at 10:37 am

Not sure what to look for?

Try our new Rash and Skin Condition Finder